Wednesday 4:21pm

By JAY REEVES and BRENDAN FARRINGTON, Associated Press

PANAMA CITY, Fla. (AP) — Supercharged by abnormally warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico, Hurricane Michael slammed into the Florida Panhandle with terrifying winds of 155 mph Wednesday, splintering homes and submerging neighborhoods. It was the most powerful hurricane to hit the continental U.S. in nearly 50 years.

Its winds shrieking, Michael crashed ashore in the early afternoon near Mexico Beach, a tourist town about midway along the Panhandle, a lightly populated, 200-mile stretch of white-sand beach resorts, fishing towns and military bases.

It battered the coastline with sideways rain, powerful gusts and crashing waves. It swamped streets and docks, flattened trees, stripped away limbs and leaves, knocked out power to a quarter-million homes and businesses, shredded awnings and sent shingles flying. Explosions apparently caused by blown transformers could be heard.

“We are catching some hell,” said Timothy Thomas, who rode out the storm with his wife in their second-floor apartment in Panama City Beach. He said he could see broken street signs and a 90-foot pine bent at a 45-degree angle.

In Mexico Beach, population 1,000, the storm shattered homes, leaving floating piles of lumber. The lead-gray water was so high that roofs were about all that could be seen of many homes.

Michael was a meteorological brute that sprang quickly from a weekend tropical depression, becoming a fearsome Category 4 by early Wednesday, up from a Category 2 less than a day earlier. It was the most powerful hurricane on record to hit the Panhandle.

“I’ve had to take antacids I’m so sick to my stomach today because of this impending catastrophe,” National Hurricane Center scientist Eric Blake tweeted as the storm — drawing energy from the unusually warm, 84-degree Gulf waters — became more menacing.

More than 375,000 people up and down the Gulf Coast were urged to evacuate as Michael closed in. But the fast-moving storm didn’t give people much time to prepare, and emergency authorities lamented that many ignored the warnings and seemed to think they could ride it out.

“While it might be their constitutional right to be an idiot, it’s not their right to endanger everyone else!” Walton County Sheriff Michael Adkinson tweeted.

Diane Farris, 57, and her son walked to a high school-turned-shelter near their home in Panama City to find about 1,100 people crammed into a space meant for about half as many. Neither she nor her son had any way to communicate because their lone cellphone got wet and quit working.

“I’m worried about my daughter and grandbaby. I don’t know where they are. You know, that’s hard,” she said, choking back tears.

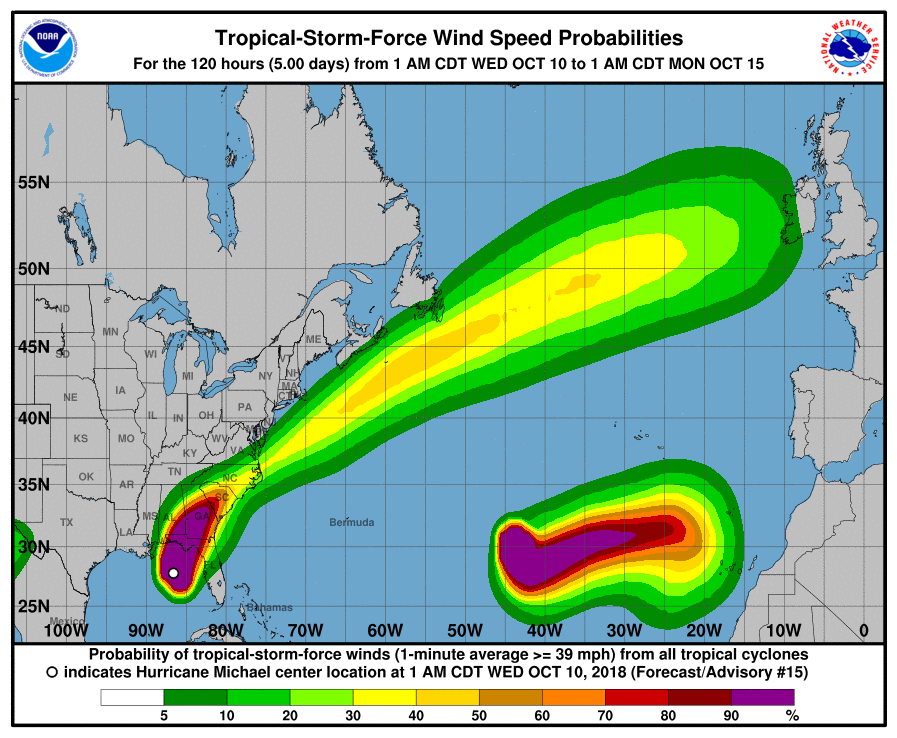

Hurricane-force winds extended up to 45 miles (75 kilometers) from Michael’s center. Forecasters said rainfall could reach up to a foot (30 centimeters), and the life-threatening storm surge could swell to 14 feet (4 meters).

A water-level station in Apalachicola, close to where Michael rolled ashore, reported a surge of nearly 8 feet (2.5 meters).

Based on its internal barometric pressure, Michael was the third most powerful hurricane to blow ashore on the U.S. mainland, behind the unnamed Labor Day storm of 1935 and Camille in 1969. Based on wind speed, it was the fourth-strongest, behind the Labor Day storm (184 mph, or 296 kph), Camille and Andrew in 1992.

It appeared to be so powerful that it was expected to remain a hurricane as it moves into Alabama and Georgia early Thursday. Forecasters said it will unleash damaging wind and rain all the way into the Carolinas, still recovering from Hurricane Florence’s epic flooding.

At the White House, President Donald Trump said the government is “absolutely ready for the storm.” ”God bless everyone because it’s going to be a rough one,” he said. “A very dangerous one.”

In Panama City, plywood and metal flew off the front of a Holiday Inn Express. Part of the awning fell and shattered the glass front door of the hotel, and the rest of the awning wound up on vehicles parked below it.

“Oh my God, what are we seeing?” said evacuee Rachel Franklin, her mouth hanging open.

The hotel swimming pool had whitecaps, and people’s ears popped because of the drop in barometric pressure. The roar from the hurricane sounded like an airplane taking off.

Meteorologists watched satellite imagery in complete awe as the storm intensified.

“We are in new territory,” National Hurricane Center Meteorologist Dennis Feltgen wrote on Facebook. “The historical record, going back to 1851, finds no Category 4 hurricane ever hitting the Florida panhandle.”

Colorado State University hurricane expert Phil Klotzbach said in an email: “I really fear for what things are going to look like there tomorrow at this time.”

The storm is likely to fire up the debate over global warming.

Scientists say global warming is responsible for more intense and more frequent extreme weather, such as storms, droughts, floods and fires. But without extensive study, they cannot directly link a single weather event to the changing climate.

With Election Day less than a month away, the crisis was seen as a test of leadership for Scott, a Republican running for the Senate, and Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, the Democratic nominee for governor. Just as Northern politicians are judged on how they handle snowstorms, their Southern counterparts are watched closely for how they deal with hurricanes.

More than 5,000 evacuees sought shelter in Tallahassee, which is about 25 miles from the coast but is covered by live oak and pine trees that can fall and cause power outages even in smaller storms.

Only a skeleton staff remained at Tyndall Air Force Base, situated on a peninsula just south of Panama City. The home of the 325th Fighter Wing and some 600 military families appeared squarely targeted for the worst of the storm’s fury, and leaders declared HURCON 1 status, ordering out all but essential personnel.

The base’s aircraft, which include F-22 Raptors, were flown hundreds of miles away as a precaution. Forecasters predicted 9 to 14 feet of water at Tyndall.

In St. Marks, John Hargan and his family gathered up their pets and moved to a raised building constructed to withstand a Category 5 after water from the St. Marks River began surrounding their home.

Hargan’s 11-year-old son, Jayden, carried one of the family’s dogs in a laundry basket in one arm and held a skateboard in the other as he waded through calf-high water.

Hargan, a bartender at a riverfront restaurant, feared he would lose his home and his job to the storm.

“We basically just walked away from everything and said goodbye to it,” he said, tears welling up. “I’m freakin’ scared I’m going to lose everything I own, man.”

___

Associated Press writers Tamara Lush in St. Petersburg, Fla.; Terry Spencer in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; Freida Frisaro in Miami; Brendan Farrington in St. Marks, Fla.; Russ Bynum in Keaton Beach, Fla.; Jonathan Drew in Raleigh, North Carolina; and Seth Borenstein in Kensington, Md., contributed to this story.

For the latest on Hurricane Michael, visit https://www.apnews.com/tag/Hurricanes .

Wednesday 8:45am

By JAY REEVES, Associated Press

PANAMA CITY, Fla. (AP) — Michael’s leading edge careened onto northwest Florida’s white-sand beaches as a still-growing Category 4 hurricane Wednesday, lashing the coast with tropical storm-force winds and rain and pushing a storm surge that could cause catastrophic damage well inland once it makes landfall.

The unexpected brute quickly sprang from a weekend tropical depression and grew to top winds of 145 mph (230 kph), the most powerful hurricane in recorded history for this stretch of the Florida coast.

The sheriff in Panama City’s Bay County issued a shelter-in-place order before dawn Wednesday, and Florida Gov. Rick Scott tweeted that for people in the hurricane’s path, “the time to evacuate has come and gone … SEEK REFUGE IMMEDIATELY.”

At 8 a.m ., Michael’s eye was about 90 miles (145 kilometers) from Panama City and Apalachicola, moving relatively fast at 13 mph (21 kph). Tropical-storm force winds, extending 185 miles (295 kilometers) from the center, were already lashing the coast, and hurricane-force winds reached out 45 miles (75 kilometers) from the center.

The storm now appears so powerful — with a central pressure dropping to 933 millibars — that it is expected to remain a hurricane as it moves over central Georgia early Thursday, and unleash damaging winds all the way into the Carolinas. Rainfall could reach up to a foot (30 centimeters), and the life-threatening storm surge could swell to 14 feet (4 meters).

“We are in new territory,” National Hurricane Center Meteorologist Dennis Feltgen wrote in a Facebook post Wednesday. “The historical record, going back to 1851, finds no Category 4 hurricane ever hitting the Florida panhandle.”

Florida officials said more than 375,000 people up and down the Gulf Coast had been urged or ordered to evacuate.

Only a skeleton staff remained at Tyndall Air Force Base, which is located on a peninsula just south of Panama City. The home to the 325th Fighter Wing and some 600 military families appeared squarely targeted for the worst of the storm’s fury, and leaders declared “HURCON 1” status, ordering all but essential personnel to evacuate. The base’s aircraft, which include F-22 Raptors, were flown hundreds of miles away as a precaution, a spokesman said in a statement.

Evacuations spanned 22 counties from the Florida Panhandle into north central Florida. But civilians don’t have to follow orders, and authorities feared many failed to heed their calls to get out of the way as the hard-charging storm intensified over 84-degree Gulf of Mexico water.

“I guess it’s the worst-case scenario. I don’t think anyone would have experienced this in the Panhandle,” meteorologist Ryan Maue of weathermodels.com told The Associated Press. “This is going to have structure-damaging winds along the coast and hurricane force winds inland.”

Maue and other meteorologists watched in real time as a new government satellite showed the hurricane’s eye tightening, surrounded by lightning that lit it up “like a Christmas tree.”

University of Georgia’s Marshall Shepherd, a former president of the American Meteorological Society, called it a “life-altering event,” writing on Facebook that he watched the storm’s growth on satellite images with a growing pit in his stomach.

Sheriff A.J. Smith in Franklin County, near the vulnerable coast, sent his deputies door to door urging people to evacuate.

“We have done everything we can as far as getting the word out,” Smith said. “Hopefully more people will leave.”

Most of the waterfront homes stood vacant in Keaton Beach, which could get some of the highest water — seas up 9 feet (2.75 meters) above ground level.

“I know it’s going to cover everything around here,” said Robert Sadousky, who at 77 has stayed through more than four decades of storms.

The retired mill worker took a last look at the canal behind his home, built on tall stilts overlooking the Gulf. He pulled two small boat docks from the water, packed his pickup and picked some beans from his garden before getting out — like hundreds of thousands elsewhere.

The local geography — low-lying land and lots of areas where people live along waterways — means many people living inland could see their homes flooded as Michael makes landfall.

“We don’t know if it’s going to wipe out our house or not,” Jason McDonald, of Panama City, said as he and his wife drove north to safety into Alabama with their two children, ages 5 and 7. “We want to get them out of the way.”

Scott had warned of a “monstrous hurricane,” and his Democratic opponent for the Senate, Sen. Bill Nelson, described a destructive “wall of water,” but some officials didn’t see any rush of evacuees ahead of the storm.

“I am not seeing the level of traffic on the roadways that I would expect when we’ve called for the evacuation of 75 percent of this county,” Bay County Sheriff Tommy Ford said Tuesday.

In the dangerously exposed coastal town of Apalachicola, population 2,500, Sally Crown planned to hunker down with her two dogs.

“We’ve been through this before,” she said. “This might be really bad and serious. But in my experience, it’s always blown way out of proportion.”

Mandatory evacuation orders went into effect in Panama City Beach and other low-lying areas in the storm’s path. That included Pensacola Beach but not in Pensacola itself, a city of about 54,000.

Michael will weaken over land but could still spin off tornadoes and dump rain along a northeasterly path over Alabama, Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia before its remnants head out to sea again. Forecasters said it also could bring 3 to 6 inches of rain, enough to trigger flash flooding in places still recovering from Hurricane Florence.

___

Associated Press contributors include Tamara Lush in St. Petersburg; Russ Bynum in Keaton Beach; Jonathan Drew in Raleigh, North Carolina; and Science Writer Seth Borenstein in Kensington, Maryland.

For the latest on Hurricane Michael, visit https://www.apnews.com/tag/Hurricanes .

Tuesday 9am

By JENNIFER KAY and GARY FINEOUT, Associated Press

MIAMI (AP) — Hurricane Michael swiftly intensified into a Category 2 over warm Gulf of Mexico waters Tuesday amid fears it would strike Florida on Wednesday as a major hurricane. Mandatory evacuations were issued as beach dwellers rushed to board up homes just ahead of what could be a devastating hit.

A hurricane hunter plane that bounced into the swirling eye off the western tip of Cuba found wind speeds rising. By 8 a.m. Tuesday, top winds had reached 100 mph (155 kph), and it was forecast to strengthen more, with winds topping 111 mph (179 kph), capable of causing devastating damage.

Gov. Rick Scott warned people across northwest Florida at a news conference Tuesday morning that the “monstrous hurricane” was just hours away, bringing deadly risks from high winds, storm surge and heavy rains.

His opponent in Florida’s Senate race, Sen. Bill Nelson, said a “wall of water” could cause major destruction along the Panhandle. “Don’t think that you can ride this out if you’re in a low-lying area,” Nelson said on CNN.

Mandatory evacuation orders went into effect Tuesday morning for some 120,000 people in Panama City Beach and across other low-lying parts of the coast as Hurricane Michael approaches.

Parts of Florida’s marshy, lightly populated Big Bend area could see up to 12 feet (3.7 meters) of storm surge, while Michael also could dump up to a foot (30 centimeters) of rain over some Panhandle communities as it moves inland, forecasters said.

“People need to start leaving now,” Sheriff Tommy Ford told an emergency meeting Monday night. He said people will “not be dragged out of their homes,” but anyone who stays behind will be on their own once the storm hits.

Forecasters warned that Michael could ultimately dump a foot (30 centimeters) of rain in western Cuba, triggering flash floods and mudslides in mountain areas.

Disaster agencies in El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua reported 13 deaths as roofs collapsed and residents were carried away by swollen rivers. Six people died in Honduras, four in Nicaragua and three in El Salvador. Authorities were also searching for a boy swept away by a river in Guatemala. Most of the rain was blamed on a low-pressure system off the Pacific coast, but Hurricane Michael in the Caribbean could have also contributed.

Scott declared a state of emergency for 35 Florida counties, from the Panhandle to Tampa Bay, activated hundreds of Florida National Guard members and waived tolls to encourage evacuations.

He also warned caregivers at north Florida hospitals and nursing homes to do all possible to assure the safety of the elderly and infirm. Following Hurricane Irma last year, 14 people died when a South Florida nursing home lost power and air conditioning.

“If you’re responsible for a patient, you’re responsible for the patient. Take care of them,” he said.

Escambia County Sheriff David Morgan bluntly advised residents choosing to ride it out that first-responders won’t be able to reach them while Michael smashes into the coast.

“If you decide to stay in your home and a tree falls on your house or the storm surge catches you and you’re now calling for help, there’s no one that can respond to help you,” Morgan said at a news conference.

In the small Panhandle city of Apalachicola, Mayor Van Johnson Sr. said the 2,300 residents were frantically preparing for what could be a strike unlike any seen there in decades. Many filled sandbags and boarded up homes and lined up to buy gas and groceries before leaving town.

“We’re looking at a significant storm with significant impact, possibly greater than I’ve seen in my 59 years of life,” Johnson said of his city on the shore of Apalachicola Bay, which where about 90 percent of Florida’s oysters are harvested.

There will be no shelters open in Wakulla County, the sheriff’s office warned on Facebook, because they are rated safe only for hurricanes with top sustained winds below 111 mph (178 kph). With Michael’s winds projected to be even stronger, residents were urged to evacuate inland.

“This storm has the potential to be a historic storm, please take heed,” the sheriff’s office said in the post.

Neighbors in Alabama — the entire state is under an emergency declaration — also were bracing. Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey said she fears widespread power outages and other problems would follow. Forecasters also warned spinoff tornadoes would also be a threat.

With the storm next entering the eastern part of the Gulf of Mexico, which has warm water and favorable atmospheric conditions, “there is a real possibility that Michael will strengthen to a major hurricane before landfall,” Robbie Berg, a hurricane specialist at the Miami-based storm forecasting hub, wrote in an advisory.

A large mound of sand in Tallahassee was whittled down to a small pile within hours Monday as residents filled sandbags against potential flooding.

Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, Florida’s Democratic nominee for governor, filled sandbags with residents and urged residents of the state capital city to finish up emergency preparations quickly. Local authorities fear power outages and major tree damage from Michael.

“Today it is about life and safety,” Gillum said. “There’s nothing between us and this storm but warm water’ and I think that’s what terrifies us about the potential impacts.”

___

Fineout reported from Tallahassee, Florida.

Mocs News Reporting the news that matters most to UTC

Mocs News Reporting the news that matters most to UTC